I haven’t been writing on here very much the last few months; I took some time off over the holidays, and I’ve been working on a longer, more ambitious article, about my great uncle’s efforts to help finance the Provisional IRA during the 1970s and ‘80s. You can read that here, in New Lines Magazine.

And, as a digestif, here is Part I of my review of the Irish journalist Ed Moloney’s opus A Secret History of the IRA, as told through a capsule history of the life of longtime Sinn Fein/IRA leader Gerry Adams.

Thank you for reading and subscribing.

Brendan

If you’re Gerry Adams—head of Ireland’s Sinn Fein party and, though he’ll deny it to the end of his days, the most powerful figure in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA)—you must, by the end of the 1990s, be pretty pleased with yourself.

What you’ve accomplished over the last thirty years—not coincidentally, just as long as the war between the PIRA and the British state—is considerable. Like your father and uncles before you, you’re inducted into the paramilitary group as a teenager. Growing up in Belfast in the ‘50s and ‘60s, you experience a kind of uneasy peace, and instinctively know which parts of town (the Falls Road, Markets/Short Strand, Andersonstown, the Ballymurphy housing estate in which you spend your childhood, etc.) are comprised of “your people,” and which are predominantly Protestant. Though violence isn’t necessarily part of that demarcating experience, it very well might be. Being of a political bent, and possessive of an analytical mind, you test your ideas in (small-r) republican debating clubs called Wolfe Tone Societies, after the great father of Irish republicanism. Shut out of the best jobs and industries as a Catholic, and born into an intensely militant republican family context, the narrow possibilities for your life at the outset are narrower still than those of other Catholics in the north. Before the war, you pull pints as a 17 year old bartender at the Duke of York pub in Donegall Street.

As Northern Irish [sic] civil society collapses around you in 1969, you quickly distinguish yourself from the many hundreds of other young men active in republican paramilitary circles, even acquiring a nickname—the “Big Lad”—which speaks to your youth and the already renowned leadership qualities that will fast-track you upward through the ranks of army leadership. As mobs burn Catholics out of their homes in Protestant areas, and bombs explode on a near-daily basis, you become familiar with the smell of charred brick, scorched metal, and melting flesh. You navigate an organizational split, leaving, with the rest of the so-called “Provisional” IRA—which emphasizes traditional republican ideals, namely the central role of armed resistance—the “Official” IRA, which increasingly advocates constitutional means (namely contesting elections) and left-wing ideas, and de-emphasizes the gun. Both groups will continue to call themselves, simply, “the IRA.” Already, you exhibit a disquieting knack for media, PR, and optics.

Measured solely as a means of maximizing your personal influence over the coming decades, you choose rightly, as the Provisionals start to earn a robust reputation for their defense of Catholic areas, most notably at the Battle of St. Matthew’s in Belfast’s Short Strand. You rise quickly, first heading the IRA in your native Ballymurphy and, in a few short years, becoming Officer Commanding (OC) of the entire Belfast Brigade, a role in which you plan operations and sanction killings—of soldiers, civilians, and probably other paramilitaries. Your alleged actions and directives of these years, especially regarding the disappearance of the widowed mother of ten and suspected informer Jean McConville, will ramify behind closed doors, in the courts, and in the media for the rest of your life—frustrating, but not foreclosing, your otherwise sparkling middle-age transition into constitutional politics.

You spend your days and nights bouncing between the dilapidated homes of your supporters in West Belfast to evade capture or assassination by the British army—or, for that matter, by your fellow British subjects, in the form of Protestant paramilitaries. You see your wife Collette rarely, and you forbid her from using or carrying weapons, though plenty of other women will. Never one to fire guns or plant bombs yourself, you garner a reputation for strategy, directing fanatical, violent soldiers like “Big” Jim Bryson, Paddy Mulvenna, and Tommy “Toddler” Tolan, all of whom are killed within a few years—Bryson and Mulvenna at the hands of the British Army in 1973, and Tolan by the Official IRA in 1977. Others replace the dead men—you have no shortage of crude instruments—but the war’s Wild West phase is over. You continue your ascent, becoming adjutant general of the entire PIRA and joining its seven-man Army Council.

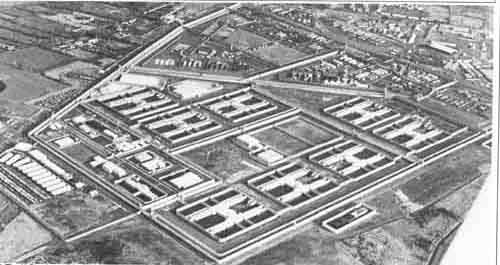

Like hundreds of other volunteers in the early 1970s, you suffer the crucible of internment, interrogation, and torture at the hands of the British security forces, though you are spared the ordeal of being dangled from a helicopter. Nor are you forced to run barefoot across fields of barbed wire and broken glass or, like the fourteen Hooded Men, subjected to each of the Five Techniques (prolonged wall-standing, hooding, subjection to noise, deprivation of sleep, and deprivation of food and drink) though probably several of them. On at least one occasion, you derail your interrogators by insisting that you are not, in fact, Gerry Adams, but a man named Joe McGuigan.

The same leadership qualities that elevate you outside of the prison camp serve you very well inside of it. With your Cage 11 comrades, and at the leadership’s request, you devise a cellular reorganization plan for the IRA that cements your long term influence over the group and its trajectory. Likewise, your experience of torture helps you to formulate comprehensive anti-interrogation methods which are set down in the IRA’s instructive “Green Book” as militant republican gospel. Henceforth, all new IRA recruits, before participating in any army activities, will first be “green booked.”

As the 1970s become the 1980s, you, Adams, having been released from internment and mastered the IRA’s ruling Army Council with the support of a few allies, trade your black beret and sunglasses for sweaters, suits, and ties, becoming vice president of the group’s political wing, Sinn Fein. Now a public figure, you deny being a member of the IRA, but you also, infamously, refuse to dissociate yourself from the IRA. You smoke a pipe, wear a beard, and castigate your political opponents within the republican movement as unsuitably militaristic and too often sectarian. Then you move to isolate, marginalize, and discredit them. In particular, you will fulminate against the IRA-British ceasefire of the mid-1970s as a near-death knell for the IRA, and in doing so proceed to win the hearts and minds of grassroots republicans and the most hardline operators who make up the IRA’s vital active service units (ASUs), the individual units of its armed struggle. Though you will hold to an outward appearance of hardline militarism within the movement, your activism from this point onward is best characterized by an ideological flexibility that facilitates whatever course of action best suits your personal ambitions at any particular moment. Without being accused of abandoning the armed struggle (which would, naturally, amount to treason), you begin to advocate for civic initiatives and a role for Sinn Fein in addressing community and constituent needs—“doing things for people”—ostensibly with an eye towards contesting elections (on, of course, an abstentionist basis). Nonetheless, you declare that peace is only possible when Britain withdraws from Ireland. As a purely technical matter, you are still, by this point, a member of the IRA—actually, as adjutant, second-in-command to your ally Martin McGuinness.

And you begin to read the tea leaves. Aside from a string of spectacular successes—the same-day assassination in 1979 of Lord Louis Mountbatten, whose fishing boat explodes off the County Sligo village of Mullaghmore (also killing two children, including the deckhand Paul Maxwell, 15, and the former Viceroy’s grandson, Nicholas Knatchbull, 14); and the Warrenpoint ambush in County Down, in which two roadside bombs kill 18 soldiers of Her Majesty’s Parachute Regiment—the war has slowed. Not even the most sanguine volunteer entertains, at this point, the possibility of imminent British withdrawal from the north, and the IRA can no longer credibly issue maximalist slogans like “Victory in ‘74!” It is correctly surmised that infiltration by elements of Special Branch, MI5 and the British army is general throughout the organization, severely damaging the IRA’s ability to execute successful “ops.”

Then events intercede. Republican prisoners from both the IRA and the avowedly left-wing Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) in HM Long Kesh (the “H-Blocks”) prison launch a series of protests aimed at recapturing their status as political prisoners rather than ordinary criminals, and with it their ability to wear their own clothes and associate freely within the prison. Faltering at first, the protests gather a momentum of their own, culminating in a hunger strike joined at staggered intervals by ten men, the first of whom is your old friend from Cage 11, Bobby Sands.

The protests are the best publicity for the militant republican movement in a generation, as headlines around the world proclaim Sands’ principled courage, while Margaret Thatcher’s reputation suffers grievously by contrast. It is also a shot in the arm for your efforts to politicize the armed struggle. Five days after Sands begins his fast, Frank Maguire, the independent republican Member of Parliament for Fermanagh-South Tyrone, dies of a heart attack. And Sands, who is in prison for illegal arms possession, is thrust forward to run for the open seat. Other nationalist parties agree to stand down and rally behind Sands, who runs on the “anti H-Block” ticket. On April 10th, 1981, he receives 30,493 votes to his opponent, the Ulster Unionist Party candidate Harry West’s 29,046—becoming, as a convicted felon, political prisoner, and hunger striker the youngest British MP.

Without taking his seat—an impossibility given his imprisonment, the bodily weakness which prevents him leaving his bed, and the ancient republican doctrine which holds Westminster to be an illegitimate body—Sands dies less than a month later after 66 days on hunger strike, at age 27. An estimated 100,000 people attend his funeral, which features an IRA guard of honour. You, Gerry Adams, help to carry his casket.

Notwithstanding your former comrade Ricky O’Rawe’s 2005 disclosure that the strike could have ended on acceptable terms sooner if not for your dissembling, six more of Sands’ comrades follow him into death, for a total of ten—the last of whom is the INLA’s Michael Devine, also aged 27, on August 20th. Once a proponent of a “long war” doctrine, and a bitter critic of all who would contest elections with the imprimatur of the IRA, you are further facilitated in your political ambitions for the movement by what happens next: Kieran Doherty, before succumbing to his fast on August 2nd, is elected to Dáil Éireann on the prisoner ticket along with the jailed IRA volunteer Paddy Agnew—neither of whom take their seats in the Irish parliament, but whose success rattles the Dublin establishment anyway. Newly emboldened, you cautiously disseminate, through your hand-picked propagandist Danny Morrison, the signals of a new, full-fledged political direction for a beefed-up Sinn Fein, exemplified in Morrison’s speech to the annual Ard Fheis in November 1981, and its explicit joining of the Armalite in one hand and the ballot box in the other. With the door open to contesting elections in Ireland and Great Britain—on, as ever, an abstentionist basis—you eye a seat for yourself in West Belfast. In 1983, you’re elected as a British MP for Sinn Fein.

As the 1980s progress, you continue to confound the realm of the possible by messaging, through priestly intermediaries, that the IRA is ready to talk to the British and Irish governments on grounds which need not include British withdrawal from Ireland—as a demand, a cornerstone of militant Irish republican policy post-1921, and a line to which you continue to resolutely hold in all public statements. The contradictions between your public and private negotiating positions are evident, for what you are attempting is nothing less than a clandestine attempt to steer the IRA, over whom you have a firm but mutable grip, into the waters of constitutional politics, for good—permanently forsaking the sacrosanct armed struggle and, to the ASUs that comprise the IRA’s hardest, most militant commandos, besmirching the sacred cause of the fallen martyrs. Denuded of all rhetoric and artifice—which are, to be clear, your specialties—these measures amount to nothing less than a total betrayal.

Moving forward anyway, messaging differently to each constituency according to their needs, your goal is to negotiate—but, more urgently, to obfuscate; to persuade all those serving in the dangerous, unromantic roles in the grassroots; those sleeping on bales of hay in remote farmhouses, clutching small arms and rifles, to those picketing and petitioning for Sinn Fein support in all 32 counties and America; and to those who appear beside you in public with guns under their jackets; that whatever happens next, up to and including the silence of IRA guns, will ultimately be worth it. To your negotiation partners in the British and Irish governments, you must be the pragmatic peacemaker, sitting on the lid of a kettle that threatens always to boil over; to the men and women who follow you in the movement, you must show them a man who has given everything to the cause of Irish republicanism, a figure of iron who will end the armed struggle on no terms short of a full British withdrawal.

It will be the greatest test of your life—requiring all of the skills of duplicity and triangulation that have helped you to reach the apex of IRA and Sinn Fein power. To put a foot wrong could not only mean losing an internal power struggle, only to return, embittered, to a West Belfast hearth, and to spend your dotage in irrelevance, but something much darker—the bane of all militant Irish republican groups, a costly split, which would destroy you before the leaders of the world as a credible negotiator, and which would see many of your most able fighters, and many hidden arms dumps, slip from your grasp. It could even cost you your life.

Until Part II…

Loved this!!!!

A wonderfully enthralling and thorough piece. GTFO GBR! Can't wait for part two!