Alex Ross Perry's Hall of Mirrors

“My cosmology is missing a Godhead, and I think Pavement could be that.”

In the middle of American rock band Pavement’s November 1999 show at the London Brixton Academy, Stephen Malkmus, the group’s lead singer and songwriter, handcuffed himself to the mic stand.

“These,” Malkmus intoned in his nasal, Californian vocal fry, “symbolize what it’s like being in a band.”

Pavement broke up shortly after, not to play again for 11 years—or longer than their first run. The cuffs stunt was cited as the breakpoint, not to mention a classic example of the pampered attitude and flair for the dramatic which once inspired Hole singer Courtney Love to christen Malkmus the “Grace Kelly of indie rock.”

…Except it may not have happened. The cuffs.

Or it may have happened, but not quite in that way. Or it may have happened in exactly that way. We don’t know.

And Pavements—a new film directed by Alex Ross Perry, which premiered last week in North America at the New York Film Festival—is not at all interested in telling us.

Where most “rockumentaries,” you see, are in the business of setting the record straight, of demystifying—of turning on a fan and opening a window to let some of the smoke out—Pavements seems only to add to the confusion.

It’s not even really a documentary, per se, but a sort of mixed-media mosaic (stay with me here): The film is part archival footage of the band during its first run; part documentary about a semi-scripted, fictionalized, Bohemian Rhapsody-style (read: bad) biopic following the members of the band Pavement; and part documentary about the staging of a Pavement-themed, off-Broadway jukebox musical.

The comedian Tim Heidecker is in Pavements, playing both himself, it would seem, and Gerard Cosloy, co-founder of Matador Records. Jason Schwartzman is in it, playing Jason Schwartzman (I think) and Matador’s Chris Lombardi.

Joe Keery, of Stranger Things megafame, plays two characters: Joe Keery playing Stephen Malkmus, and Stephen Malkmus. If he breaks character at any point (it’s unclear), that would bring the number to three.

Get it now?

The film appears to be Perry’s answer to a kind of immense dilemma, a bonafide Gordian knot which would only yield to a technically creative, bespoke solution, and which begins with a question: what sort of documentary would suit a band that defies description? a band whose very catalogue is, itself, a postmodern regurgitation of all rock, and which delights in subverting all of rock’s tropes? a band that slagged on critics, the industry, and even commercial success itself? who couldn’t even get through their own songs without changing the lyrics as a piss-take?

Malkmus, in a pre-production text to Perry, gave one simple direction: Avoid legacy trap[.] Film editor Robert Greene, somehow, keeps it all hanging together, in a technical feat (there’s that T-word again) for the ages.

That approach satisfied me: with a story like this, in which the band and its oeuvre is providing all the Major Art vibes required, you don’t really need a film to perform high-brow somersaults. And Perry more or less acquiesces—despite all the chatter about how innovative the film is, the narrative structure is actually pretty basic.

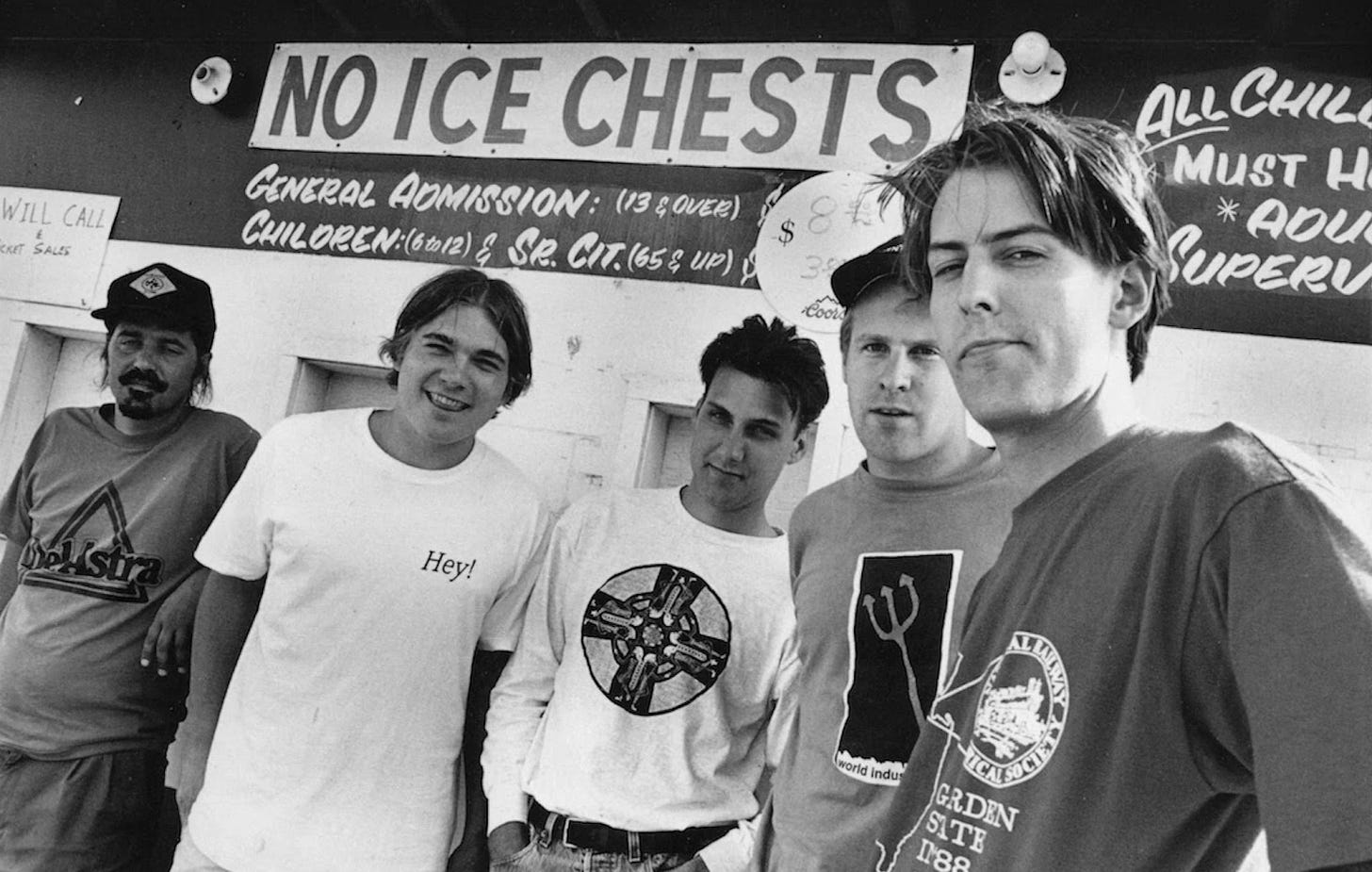

It tells the band’s story in more-or-less chronological order—from their suburban childhoods in Stockton, CA, to college radio and punk shows in Charlottesville, VA; working as guards at the Whitney Museum to their first gigs with Sonic Youth and, a little later, Nirvana; from basically bombing The Tonight Show with Jay Leno in ‘94 to actually-sorta-trying at Lollapalooza ‘95 and, in response, being pelted to death with mud in Charles Town, WV.

Pavements also charts the band’s recent resurgence, following their 2022 world tour—which, as it happens, is the first time yrs truly got to see them in concert (I saw them again in 2023). Around the same time, director Alex Ross Perry set up a Pavement museum in downtown Manhattan featuring lots of real (but mostly fake) artifacts, provoking many earnest fan reactions (“I didn’t know Pavement won an MTV music award!”) which he then filmed covertly, confusing me and lots of other people and including some of those shots in the movie.

Meanwhile, as Perry fleshed out his sensational alternate reality where the basically obscure historical phenomenon known as “Pavement” was actually Cobain-sized, something extremely odd was underway: TikTok adjusted its algorithm, and by some strange interceding alchemy, one of Pavement’s most obscure songs, a B-side called “Harness Your Hopes,” went extremely, extremely viral. As ever, there was a prominent dance element.

As things stand, “Harness”—a song that Malkmus once thought so little of that he declined to release it at all—has about 150 million streams on Spotify, or about 3X that of their next-most popular song, “Cut Your Hair,” which the band once played on MTV, when there was genuinely a lot of big label hype and big money swimming around alt-rock bands. Coming on the heels of their critically respected but commercially inert debut album, Slanted and Enchanted, “Cut Your Hair” was supposed to be their “Smells Like Teen Spirit”—paving the band’s way to riches, leisure, and global fame.

It didn’t work out that way. But earlier this year, solely on the strength of an online trend driven by folks even younger than me, “Harness” became the band’s first RIAA-certified Gold—twenty-six years after it was first recorded (and promptly discarded). As if that weren’t weird enough, Greta Gerwig wrote a Stephen Malkmus joke into ultra-smash hit Barbie (2023), name-checking a musician’s musician—famous only to a certain type of, um, cultural antiquarian—in a film that would go on to gross $1.5 billion worldwide.

The film handles this all rather artfully, making clear that geriatric Gen-Xers like Malkmus and guitarist Scott Kannberg were more baffled than anything by their renewed fame, which was threatening to take on proportions eerily similar to those they were meant to achieve piggybacking off the Nirvana moment, but never quite did. (Perhaps the most poignant moment comes when Kannberg, clearly reflecting on some sort of rock-bottom, describes his former intention to march downtown and sign up to become a Seattle bus driver—just before the phone rang on a second Pavement reunion tour.)

“The movie changes while you make it,” Perry said onstage at NYFF. In other words, his metafictional alternate reality was beginning to bleed into our own.

Film reviews are really only worthwhile if they can answer, for the reader, one basic question: Should I go see it?

To which I answer: Yes, you should, provided you care something for rock music and American pop-cultural history—or if you think Joe Keery (who’s genuinely very funny in this) is, like, a total dreamboat. Or if you just love metafictional world-building, or really strong editing.

One of its strengths is that it’s a fan’s film, but turned inside-out: It takes every Pavement trope and makes of them sock-puppets, which the film’s figures then inhabit, inventing lots of dialogue and basically making the band’s fraught history into a kind of pantomime—satisfying those who already know the full story by presenting tired-out narratives in a fresh, funny way, and being captivating enough at the basics to entertain newcomers.

I liked the movie. Maybe I didn’t love it. I think anything that purports to carefully handle material that is so near and dear to yourself may instead end up reading as some kind of spurious ego threat—more than anything, given the stakes involved, maybe it’s an endorsement of the film that I didn’t hate it.

But it’s not clear that Malkmus liked it, at all. He was silent during the Q&A with festival creative director Dennis Lim, almost sulking in his chair as “questions for the band” bounced off him left and right. What he did say was almost entirely ambivalent. Apparently, there was a full cut of the pointedly shitty biopic that was screened last year, in Brooklyn, as if it were the genuine article. And the band—Malkmus foremost, it seems—took it as some kind of prank. “There’s no need to relitigate all that,” said Perry during the Q&A, evidently trying to preempt something.

One quote in the film I’ve kept coming back to is uttered by someone who may not even fully appear onscreen, if memory serves. It was a young guy, possibly of disembodied voice (the proverbial Ur-dude, maybe?), who said something like: “My cosmology is missing a Godhead, and I think Pavement could be that.”

It was like getting hit in the chest, hearing that. (Warning—here comes the gooey, overly sentimental crap).

I felt much the same way once, growing up in my own banal corner of suburbia. As a 16 year-old, the only spiritual needs I had were those I fed at the lonely altar of my mother’s 2009 Jeep Liberty, as I’d leave the house with a half-full tank and kinda, just… drive. Fuck an aux cord—I’d burn all my favorite Pavement tracks onto CDs, like a true ‘90s kid, even if hitting an ice patch made the song skip (which it often did).

I’d decline all social invitations, preferring the company of these guys from Stockton, California who went to the University of Virginia in the ‘80s, and who took the raw materials of the American dream (empty homes, plastic cones, stolen rims—are they alloy or chrome?) and rendered them into long, looping reveries and brief, jazzy punk exorcisms.

They weren’t dorks, but well-read pseudo-jocks. Cocksure and clever punks. Literate jesters of the underground. “Privileged,” you might say. And definitely not cool in an obvious, 21st century kind of manner (they were, after all, “white dudes” making “guitar music”), but they certainly fit the only version of cool that interested me. They were a bit bratty, a bit snotty, along with lots of other words that also applied to yours truly.

But they were up to something noble, I thought, fighting a fight that seemed worthy—less a culture war than a cultural crusade against the forces of middle management, of mass-marketed mediocrity. On 1994’s “Range Life,” Malkmus let loose a few sharp arrows at the dour, lumbering industry behemoths of the time:

Out on tour with the Smashing Pumpkins / Nature kids, they don’t have no function.

I don’t understand what they mean / And I could really give a fuck

and

The Stone Temple Pilots / They’re elegant bachelors

They’re foxy to me / Are they foxy to you?

I will agree / They deserve absolutely nothing

Nothing more than me

And they misidentified targets, too. Pavement auxiliary drummer and back-up vocalist extraordinaire Bob Nastanovich fondly recalled a story, in 2015, about the pre-fame Pavement (plus David Berman, also of UVA and Silver Jews) hanging out at a pre-Nevermind Nirvana show in 1990, where they proceeded to heckle the trio that would, in a few years’ time, become the biggest band in the world.

They heckled [Nirvana] for fun, which apparently led to Krist Novoselic and Berman insulting each other back-and-forth. (Malkmus was also there—he distanced himself from Berman.)

Kurt Cobain apparently got angry, the band only played about four songs, and they destroyed their equipment. “We were outside drinking our dollar beers, congratulating each other, and literally in droves, people would come by us and tell us how much they hated us,” [Nastanovich said].

Needless to say, this was the sort of behavior that a teenager with a rebellious streak found highly enticing. I admire it much less now, though I still cherish its more elegant expressions, as found both on “Range Life” and elsewhere. And there were no hard feelings—Kurt allegedly hand-picked Pavement to appear alongside him at Reading ‘92.

But if this, shall we say, spirited maladjustment is sometimes a bug, sometimes a feature of the Pavement style in American music, at least they unapologetically stood for something, call it “authenticity”—a rarity in the leafy Connecticut suburbs I inhabited, where everybody had options (so many options!), and made a habit of keeping those options open.

I knew that Pavement, anti-social as they might have seemed—not to mention their actual playing, with its quirky off-key tunings, ample use of distortion, and often cartoonish vocal effects—preserved, in their profound refusal, a certain kind of integrity.

Now, with Pavements, there’s a pretty good contemporary film about them. And in inflating their legend even further with one scene, only to turn around in the next and pop it with a needle, Alex Ross Perry may be their star pupil.

Brendan, I love “spirited maladjustment” so dang much. Thank you for that. Speaking from experience, once the listener’s own maladjustment falls under the influence of this particular spirit (ouch, sorry, had to do it… also kinda fits in with the religion motif too though), Pavement replaces Nirvana as the zeitgeist of the 90s.

Great article!!!